I’ve spoken many times about analyzing what we see and read and using that to inform our own writing. In the novel and film, we are entertained by two brilliant versions of the story of Clarice Starling, Buffalo Bill, and Dr. Hannibal “The Cannibal” Lecter. That’s a pretty unusual accomplishment. I can think of great movie adaptations of mediocre books (The Godfather and Gone Girl) and mediocre adaptations of great books (Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and The DaVinci Code).  And there are plenty of mediocre adaptations of mediocre books that just caught the right mood in Hollywood (Eat Pray Love and Life of Pi). But a great book that becomes a great film—that’s very unusual (Gone with the Wind). The Silence of the Lambs is one of those unusual exceptions. I can go back and forth reading the novel and watch the film and never worry that one will diminish the other. The only thing that diminishes the enjoyment is when I read or watch Hannibal, the disappointing sequel.

And there are plenty of mediocre adaptations of mediocre books that just caught the right mood in Hollywood (Eat Pray Love and Life of Pi). But a great book that becomes a great film—that’s very unusual (Gone with the Wind). The Silence of the Lambs is one of those unusual exceptions. I can go back and forth reading the novel and watch the film and never worry that one will diminish the other. The only thing that diminishes the enjoyment is when I read or watch Hannibal, the disappointing sequel.

The Silence of the Lambs is different

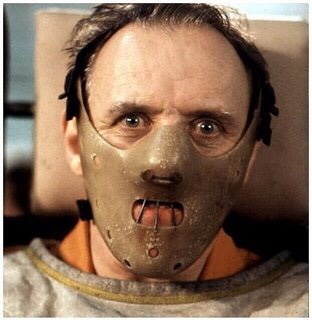

But The Silence of the Lambs is almost perfect as a novel and actually perfect as a film. The film truly has no missed notes, while Harris has a few loquacious moments in the novel. Both are at their best when they keep to their economy, focus on two riveting characters, and maintain an ever-quickening pace. We’ve reached a point in movie adaptations where longer is almost always better. Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption is around 180 pages, but the adaptation is well over two hours and omits many things (though it’s still great). The Silence of the Lambs, the film, is less than two hours long, while the novel is almost 350 pages. And yet, nothing seems missing. The adaptation by Ted Tally is perfect. The direction by Jonathan Demme never misses a beat. The performances are great all around, but Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins are at their very best. I think there is a lot for writers to learn about craft from this piece because it does the hardest thing a novel can do: it is a genre piece that has significant literary value.

We’ve reached a point in movie adaptations where longer is almost always better. Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption is around 180 pages, but the adaptation is well over two hours and omits many things (though it’s still great). The Silence of the Lambs, the film, is less than two hours long, while the novel is almost 350 pages. And yet, nothing seems missing. The adaptation by Ted Tally is perfect. The direction by Jonathan Demme never misses a beat. The performances are great all around, but Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins are at their very best. I think there is a lot for writers to learn about craft from this piece because it does the hardest thing a novel can do: it is a genre piece that has significant literary value.

What makes something genre vs literary?

To me, the defining difference between genre and literary is plot-driven vs character-driven. I know I’ve said this before but it bears repeating that for something to be truly great it should be a plot-driven piece with great characterization or a character-driven piece with a solid plot. They hardly ever happen. The Great Gatsby, though not one of my favorites, is an excellent example of a literary novel with a great plot, as is 1984. Most anything written by James Joyce does not fall into this category. Not that his works are all bad, but his focus is never on plot, and in many ways, it seems incidental. On the flip side are great genre pieces that have real aesthetic value. I would put Stephen King in this category because he’s the rarest of all writers: a genre writer who sucks at writing plot. But there are a few that can do both, though their œuvre is usually hit or miss. Tana French’s In the Woods and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale are both squarely in this category. And so is The Silence of the Lambs. There are several things Harris does extremely well in this book that other writers should use.

And so is The Silence of the Lambs. There are several things Harris does extremely well in this book that other writers should use.

How Harris transcends genre

The first is that he understands that Lecter, as the antagonist, is an overpowering character and so there must be a very powerful character in the protagonist. By making the character a woman, it allows us some real insight into Lecter‘s mind as he toys with Starling. Throughout the movie, we’re made to think that he is manipulating her to get a better room. But the truth is he’s using her to manipulate Chilton into manufacturing his escape. But he doesn’t allow Starling to get sucked into Lecter’s depravity (one of the reasons the sequel is awful) and he never lets the reader sympathize with Lecter by ever justifying his actions (one of the reasons the prequel, Hannibal Rising, is appalling).There is something very comfortable in the fact that Lecter is bad because he’s bad.  “Nothing happened to me, Officer Starling,” Lecter says when she attempts to find out why he is the way he is. Lecter rejects a behavioral analysis: he’s just evil. Starling is just good. And they work together to find a serial killer. But Lecter already knows who the serial killer is. He only lets Starling discover his identity on his own terms, not so much to toy with her, as to orchestrate his escape. All of this dovetails so well with who the characters are that it’s breathtaking when one steps back and looks all the big picture.

“Nothing happened to me, Officer Starling,” Lecter says when she attempts to find out why he is the way he is. Lecter rejects a behavioral analysis: he’s just evil. Starling is just good. And they work together to find a serial killer. But Lecter already knows who the serial killer is. He only lets Starling discover his identity on his own terms, not so much to toy with her, as to orchestrate his escape. All of this dovetails so well with who the characters are that it’s breathtaking when one steps back and looks all the big picture.

How do writers use this

To me, this all goes back to planning. I may be wrong but I don’t see how Harris could’ve written a story that so perfectly meshes plot and character without a lot of planning. And seeing as how Harris has only published five books since 1975, I think that’s safe to say. From Black Sunday in 1975 to Hannibal Rising in 2006, he averages almost 8 years between novels and hasn’t published a new one in over 11 years. Stephen King said about Harris’s process that essentially tortures himself. You can see that in the results. And that what we should take from this brilliant novel: take your time crafting your work. Plan out the details, write the damn thing, and then obsessively edit it until it’s where you want it. I would love to see early drafts of The Silence of the Lambs because I bet it was four to five hundred pages at one point and Harris whittled it down to until every single word was absolutely necessary. There are moments where he’s describing Baltimore where this reader notes the tedium. But then there’s one scene. A scene that may be perfect in its terse description and pulse-raising narrative. When Starling comes upon the storage unit that belonged to a patient of Lecter’s who he says is linked to the serial killer. We don’t know what Starling is going to find in the unit, but Harris does an amazing job of making the reader feel claustrophobic and terrified. We don’t know if she’s going to be trapped or if Lecter has set her up, but when we see that he has indeed sent her in the right direction, we begin to trust Lecter as Starling does.  Brilliant. So, as you go forward in your writing pay attention to the lessons of Thomas Harris:

Brilliant. So, as you go forward in your writing pay attention to the lessons of Thomas Harris:

• Pay attention to detail, but not to an excruciating point • Readers will only continue to read as long as they’re invested in the characters • Readers will never stop reading I those characters are in danger